South Korea has been something of a fintech laggard compared to its neighbors in East Asia. Demand for native digital banking services among Korean consumers and businesses is robust, but regulators have erred on the side of protecting incumbents. South Korea's Financial Services Commission (FSC) even rejected all the applicants for virtual-banking licenses earlier this year.

The arrival of open banking could give South Korea's financial services sector a much needed shot in the arm, improving consumer choice and pushing banks to up their game. Customers would be able to manage multiple accounts and withdraw and transfer money from a single smartphone app.

There is no doubt that fintech has boosted financial inclusion in China. Affordable banking services provided by the digital finance duopoly of Alibaba and Tencent have helped millions of individual Chinese and small businesses gain access to credit that traditional lenders would never have extended to them. In Tencent's case, its WeBank has performed a rare feat for a fintech: It has quickly become profitable (in under five years), built tremendous scale and largely escaped the ire of regulators.

India is the world's largest recipient of remittances. In 2018, Indians overseas sent home a record US$79 billion, according to the World Bank. The majority of remittances to India originate in the wealthy Gulf states of the Middle East, where there are many Indian workers. The No. 2 source of remittances to the subcontinent is the United States, followed by the United Kingdom, Malaysia, Canada, Hong Kong, and Australia.

Given the size of India's remittances market, there is a significant opportunity for fintechs, especially as the typical cost of sending remittances remains high. Fintechs who could offer remittances on the blockchain for a fraction of the fee of banks or other transfer services could tap a potentially lucrative market.

Policymakers in Beijing have long chafed at the preeminence of the U.S. dollar in the global financial system. Before the presidency of Donald Trump, it was something that they grudgingly accepted. After all, they weren't ready to let the renminbi float and open their capital account. And they still aren't. Both actions would be necessary to challenge the dollar's dominance as a global reserve currency.

Yet, amidst rising tensions with Washington that are creeping into the financial sector, Beijing is moving to challenge "dollar hegemony" in other ways. Finding a way to circumvent Washington's control over global financial flows is a priority. In late October, Russian media reported that China, Russia and India have decided to work together to develop an alternative to the SWIFT interbank messaging network that undergirds international finance. While Belgium-based SWIFT is independent, the U.S.'s rivals - and even some its allies - say that Washington has too much influence over the organization.

Hong Kong's major banks have long enjoyed high profits. Competition has been limited. A few heavyweights dominate the sector: HSBC, Standard Chartered, Bank of East Asia, Hang Seng. With the arrival of virtual banks earlier this year, the market was already on the cusp of a sea change. Retail banks realized that they would have to up their game to stay dominant. Then political turmoil swept over the former British colony in June, bringing into question its viability as a global financial center.

Choppy waters lie ahead for Hong Kong's banks, which have been battered by protests, the Sino-U.S. trade war and the slowing Chinese economy. It's unlikely that Hong Kong banks' profits per employee will remain higher than any other market. That was what Citigroup analysts found in 2018, a recent Wall Street Journal report noted.

Indonesia just might have the world's hottest P2P lending sector at the moment. We haven't seen this kind of growth in P2P since before a series of huge scams marked the beginning of the end for China's P2P market. From January to May, the Indonesia P2P sector expanded 44% to reach IDR 41 trillion (US$2.92 billion), according to Indonesia's Financial Services Authority (OJK). That healthy growth represents a moderation from the 645% increase in the year to December 2018.

The Philippines is the world's No. 4 remittance market and growing fast, offering ample opportunities for fintechs. In August, Filipinos overseas remitted $2.88 billion, up 4.6% over $2.76 billion received in the same period a year ago and the highest since May, according to government data. About 10 million Filipinos work abroad. Remittances are the Philippines’ top source of foreign exchange income. A steady inflow of dollars into the Philippines from overseas helps protect the economy from external shocks, analysts say.

At present, banks and transfer services dominate the Philippines' remittance business. The Philippines received US$34 billion in remittances last year (behind Mexico, China and India), according to the World Bank. Imagine if fintechs could capture even a modest portion of that business.

When it comes to financial reform in China, the devil's not in the details. It's in the implementation. When Beijing wants to enact change in the financial system, it can do so quickly. Consider the rise of fintech in China over the past five years. It's transformed the Chinese financial system. Unfortunately, foreign firms largely missed out on that opportunity. Paypal, who just got approval to enter China, is arriving a bit late to the party. Never mind that, say some observers. If only Paypal can get 3-5% of that market of 1.4 billion people, it will have a sizable business, they say. If only.

That brings us to the latest chapter in the Chinese financial reform saga. In early October, China’s securities regulator announced it would scrap foreign ownership limits on fund management companies from April 2020. Global asset managers would very much like increased access to China's massive $2 trillion retail fund market. This would seem to be their chance.

Singapore is expecting sub 1% economic growth this year, but you wouldn't know it from the city-state's booming fintech sector. Research firm Accenture estimates that investors sank $735 million into Singapore fintechs from January-September, up 69% year-on-year and surpassing the $642 million for all of 2018. The top areas for investments are payments (34%), lending (20%) and insurtech (17%).

Korea's Financial Services Commission (FSC) surprised some observers by rejecting all of the applicants for a virtual banking license earlier this year. The FSC had different reasons for saying no to the applicants. In the case of Toss, a peer-to-peer money transfer app owned by Korean fintech unicorn Viva Republica, the FSC worried about the ownership structure of Toss Bank and its funding capabilities.

In Asia's red-hot fintech scene, Taiwan flies largely under the radar. That's largely because no unicorns have yet emerged among its fintech startups, or any other startups for that matter. Taiwan did introduce a fintech regulatory sandbox in late 2017 and more recently established regulations for security token offerings (STOs), but the policies have yet to activate the fintech market. Fintech investment in Taiwan remains limited, especially compared to regional hubs like Singapore and Hong Kong.

If there ever was a market that could benefit from open banking, it would be Hong Kong. A small group of powerful incumbents has long dominated retail banking in the former British colony, leaving consumers frustrated with the lack of options. Data from Goldman Sachs show that HSBC, Standard Chartered, Bank of China and Hang Seng Bank account for 2/3 of retail banking loans in Hong Kong. Those four banks are even more dominant in the credit card and retail mortgage markets.

Among Asian banks, Singapore's DBS is among the most active in fintech. It has a partnership with Indonesian ride-hailing giant Go-Jek, a fintech accelerator in Hong Kong and a tech-driven Innovation Plan covering machine learning, cloud computing and API development. It has thus far created a platform of 155 APIs across roughly 20 categories. Given that DBS is well ahead of the curve when it comes to financial technology development, should it be concerned about Citibank's recent deals in its neighborhood?

Demand for cross-border remittances is surging across Southeast Asia, home to a sizeable migrant worker population and many of the world's fastest growing economies. The amounts being remitted by the region's 21 million migrant workers are considerable - $68 billion annually, according to Siam Commercial Bank (SCB). Given their modest earnings, migrant workers need affordable banking services. They cannot easily absorb the high fees associated with some traditional remittance services.

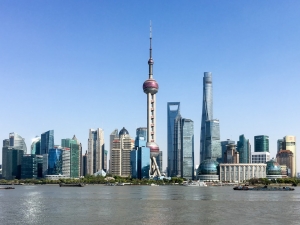

In the early 2010s, back when Donald Trump still hosted The Apprentice and the title of "Tariff Man" belonged to Herbert Hoover, China was pursuing high-profile financial reform. Shanghai, tasked by the central government with becoming a global financial center by 2020, was abuzz with the sound of renminbi internationalization. The Lujiazui financial district regularly hosted forums where participants benchmarked the growing use of the yuan in trade settlement, the rise of offshore yuan trading hubs in Hong Kong and London and the renminbi's path to global reserve currency status.

Financial reform in China has been stalled for years. Foreign banks have never managed to hold more than about 2.4% of the market - and that was back in 2007. KPMG estimates their share of domestic assets actually fell to just 1.32% by the end of 2017. The renminbi internationalization process gives new meaning to the term "incremental." The exchange rate remains controlled and the capital account closed, just as they were a decade ago when Beijing began promoting the yuan's use globally.

Yet, there are signs of change. In September, Beijing granted Deutsche Bank and BNP Paribas the right to underwrite onshore debt in China, a first for foreign banks in the world's second largest economy. Later in the month, China removed limits on two institutional investment policies that allow foreigners to invest in Chinese financial markets: the QFII scheme (dollar-denominated) and RQFII (yuan-denominated). Those moves follow Beijing's decision to allow foreign banks to take majority stakes in local securities joint ventures.

In China's peer-to-peer lending sector, there's no such thing as too big to fail. Chinese authorities have since last year been cracking down on widespread impropriety in the once ascendant segment. Even the preeminent platforms have not escaped unscathed, leaving many observers wondering if we have reached P2P's twilight in China.

Two years ago, Laos was removed from the Financial Action Task Force's (FATF) money-laundering grey list after the landlocked Southeast Asia country showed some improvement in its AML policies. Since then, however, progress has been limited. Laos's casinos, property market and money exchange shops remain at high risk for money laundering. No money laundering case has made it to court. The onus is on Laos to better control financial impropriety ahead of a 2020 evaluation of its AML policies. Failure to do so could result in a return to the grey list.

Not even the failure to obtain a virtual-banking license can dampen investor interest in South Korea's fintech unicorn Viva Republica and its digital banking platform Toss. In mid-August, Viva Republica announced it had raised $64 million from a group of investors led by Hong Kong-based Aspex Management. The latest capital injection brings Viva Repubica's total valuation to US$2.2 billion and follows an $80 million funding round in December co-led by Korean investors, Kleiner Perkins and Ribbit Capital.

Myanmar is at risk of landing on the Financial Action Task Force's watchlist high-risk money-laundering destinations after a three-year reprieve, analysts say. In 2016, FATF removed Myanmar from the list, citing improvements in the country's efforts to combat financial crime. Since then, however, Myanamar has not taken adequate steps to implement safeguards against money laundering in both its banking system and non-financial institutions. If Myanmar appears on FATF's "grey list" again, investors could sour on the Southeast Asian nation's financial sector, which would harm fintech development as well as broader financial inclusion initiatives.

In July, Taiwan's Financial Supervisory Commission (FSC) granted three virtual-banking licenses, surprising some observers who expected the regulator would only issue two. All three teams that applied for the licenses - led respectively by Japanese super app Line, Taiwanese telecoms firm Chunghwa Telecom and Japanese e-commerce giant Rakuten - were well qualified, such that the FSC felt they all deserved to launch neobanks in Taiwan.

South Korea's financial regulators have taken a conservative approach to digital banking, issuing a limited number of licenses and outright rejecting a number of recent applicants. One of the only two firms to win a digital banking license thus far is Kakao Bank, a subsidiary of the Korean super app KakaoTalk. With its massive user base - which counts 94% of South Korea's population of 50 million as users - Kakao is poised to stake out a dominant position in the nascent South Korean digital banking market.

As the Sino-US trade war steadily escalates, tensions are inevitably spilling into the financial sector. While much press coverage has focused on the U.S. naming China a currency manipulator - something that hasn't happened since 1994 - there has not been any punitive action following the designation. The decision by Washington looks more like a pointed criticism of China's long-stalled financial reforms. Remember when it was common to hear bankers speculate that China's capital account would be freely convertible by 2020?

Those were the days. Regardless, monetary policy is actually less of a flashpoint in the trade war than compliance. The alleged involvement of three major Chinese banks in the financing of North Korea's nuclear weapons program - in violation of sanctions on the Hermit Kingdom - has the potential to entangle some of China's largest lenders in a new front of the trade war.

Cambodia is struggling to contain a mounting money laundering problem. In July, authorities seized $7.4 million in cash and detained nine people at Phnom Penh and Siem Reap airports as part of anti-money laundering (AML) efforts. Cambodian authorities have stepped up AML activity since February when the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), an international money-laundering watchdog, placed Cambodia on its gray list after it found "significant deficiencies" in the kingdom's AML ability.

Cambodia had previously been on FATF's gray list but was removed in 2015 after making some improvements to its AML policies. FATF put Cambodia on the gray list once again in February after the organization concluded the kingdom had never prosecuted a money-laundering case. FATF also found that Cambodia had done little to investigate cases of money laundering and terrorist financing, while the watchdog described the Cambodian judicial system as having "high levels of corruption."

In early August, Australian challenger bank Judo announced it had completed a second round of equity fundraising that brought in a record $400 million, double the original target of $200 million. In this new round of fundraising, the largest ever for an Australian startup, Bain Capital Credit and Tikehau Capital joined existing shareholders OPTrust, the Abu Dhabi Capital Group, Ironbridge and SPF Investment Management.

For Indonesian ride-hailing giant Go-Jek, the more funding rounds the merrier. As it seeks to gain a leg up on its arch-rival Grab, Go-Jek is tapping a wide variety of investors bullish on the Indonesian decacorn's digital banking prospects. In its latest funding round, the second half of Series F, Go-Jek attracted an estimated $3 billion (the company has not disclosed the actual figure) from investors including top Thai lender Siam Commercial Bank, Visa and three Mitsubishi firms: Mitsubishi Motors, Mitsubishi Corp. and Mitsubishi UFJ Lease & Finance.

The Chinese gambling hub of Macau has a well deserved reputation for illicit activity. Although the territory has prospered in the two decades since returning to Chinese rule, overtaking Las Vegas to become the top gaming destination globally, the sources of its riches have sometimes been questionable. Corrupt officals and businessmen as well as criminal organizations launder money through the territory, taking advantage of its lax regulatory environment. Macau has no currency or exchange controls, while its threshold for reporting transactions in casinos is more than US$62,000, compared to an international standard of US$3,000.

On July 20th, Chinese State Council announced 11 measures to advance the further opening-up of Chinese financial industry to the world. 8 of the 11 policies are related to bond, asset management, and currency brokerage. The momentum of increasing foreign investment will not cease in the foreseeable future but be boosted with the newly released policies.

In the emerging world of super apps, Japan's Line is something of an anomaly. It is neither a wholly domestic phenomenon like China's WeChat nor global like the U.S.'s WhatsApp. It is not a ride-hailing app like Singapore's Grab or Indonesia's Go-Jek. Rather, Line is a quirky messaging app beloved in its home market of Japan as well as in Taiwan and Thailand, where Japanese culture has enduring appeal, and to a lesser extent in Indonesia. Outside of those markets, it is virtually unknown.

WeChat has proven that a messaging app can become a digital wallet and that the road to monetization runs through fintech. Line aims to show that such a platform is viable regionally in Asia. Because Japan remains attached to cash, Line cannot rely on its home market alone. “Fintech itself is a proven monetized model, the only problem is how fast we can secure a meaningful size of users,” Line co-CEO Shin Jung-ho told Bloomberg in a June interview.

Virtual banks are coming to Singapore, but the biggest incumbents have little to fear. Singapore's top three lenders, DBS, UOB and OCBC, have plenty of cash to invest in fintech innovation. What they cannot build independently they can access through tie-ups with startups. For smaller lenders who lack the heavyweights' resources, the virtual banks could pose a tougher challenge. The scope of the challenge will depend on how much freedom the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) gives the new entrants.

More...

At a time where China’s financial institutions face increased competition from rising fintech companies, banks in China have been battling with fintechs for market share. The surge of fintech companies have facilitated the process of acquiring loans by providing consumers with an alternative to credit cards. They also do not exclude the unbanked population of the country which is a further competitive advantage for fintech companies. Therefore, banking segments efforts to outdo fintech has forced them to take riskier measures by expanding their lending platform to unsecured loans. Creating incentives for increased consumption has consequently resulted in a higher issuance of credit cards.

Taiwan has a fairly well developed financial industry. This small island has a population of only 24 million in total, but has access to more than 5,000 physical financial institutions. Customers, therefore, are able to enjoy all the banking services provided with ease. Plus, the interest rates on loans in Taiwan are extremely low with only 2.63% APR. The application for a fiduciary loan becomes relatively easy for office workers. Thus, FinTech derivatives such as P2P lending are not previously widely considered.

Imagine you are sick at midnight. You lay in the bed comfortably and consult your private doctor through your smart phone at home. They know your medical history perfectly and give you a personalized prescription online. You don’t need to go to the pharmacy. With a few clicks on an app you purchase drugs and they arrive at your doorstep within an hour and everything is seamless. This is not necessarily a futuristic movie, but rather - reality made possible by PingAn Good Doctor - the largest and artificial intelligence powered mobile medical platform in China.

In April, the Hong Kong-based fintech startup WeLab quietly won the former British colony's fourth virtual-banking license. Founded in 2013 by ex-Citibank executive Simon Loong and two other partners, the company has steadily grown over the last six years. It now has 30 million customers in Hong Kong and mainland China as well as a staff 600 strong. The company expects to launch its virtual bank - named WeLab Digital - between October and January.