Latest Insight

- Why an expected APAC fintech consolidation wave has yet to come

- Why cash is still prevalent in Asia

- Japan steps up green finance efforts

- South Korea charts middle path on crypto

- Should Grab and GoTo merge?

- Singapore pushes ahead with fintech-driven sustainability

- Digital banks in South Korea continue to thrive

- Billease is the rare profitable BNPL firm

- Fintech sector in Pakistan faces mounting challenges

- Where digital banks in Asia can make a difference

Latest Reports

-

Breaking Borders

Despite progress in payment systems, the absence of a unified, cross-border Real-Time Payments (RTP) network means that intermediaries play a crucial role in facilitating connectivity. This report examines the ongoing complexities, challenges, and initiatives in creating a seamless payment landscape across Asia. Innovate to Elevate

Despite progress in payment systems, the absence of a unified, cross-border Real-Time Payments (RTP) network means that intermediaries play a crucial role in facilitating connectivity. This report examines the ongoing complexities, challenges, and initiatives in creating a seamless payment landscape across Asia. Innovate to Elevate In the dynamic and diverse financial landscape of the Asia-Pacific (APAC) region, banks are at a pivotal juncture, facing the twin imperatives of innovation and resilience to meet evolving consumer expectations and navigate digital disruption. Catalyzing Wealth Management In The Modern Era

In the dynamic and diverse financial landscape of the Asia-Pacific (APAC) region, banks are at a pivotal juncture, facing the twin imperatives of innovation and resilience to meet evolving consumer expectations and navigate digital disruption. Catalyzing Wealth Management In The Modern Era Hyper-personalized wealth management presents a paradigm shift from traditional models relying on static, generalized segments. Developing tailored investor personas based on psychographics, behaviours and fluid financial goals enables financial institutions to deliver rich and tailored customer experiences that resonate with next-generation priorities.

Hyper-personalized wealth management presents a paradigm shift from traditional models relying on static, generalized segments. Developing tailored investor personas based on psychographics, behaviours and fluid financial goals enables financial institutions to deliver rich and tailored customer experiences that resonate with next-generation priorities.

Events

| April 23, 2024 - April 25, 2024 Money 2020 Asia 2024 |

| October 21, 2024 - October 24, 2024 Sibos Beijing |

| November 06, 2024 - November 08, 2024 Singapore Fintech Festival |

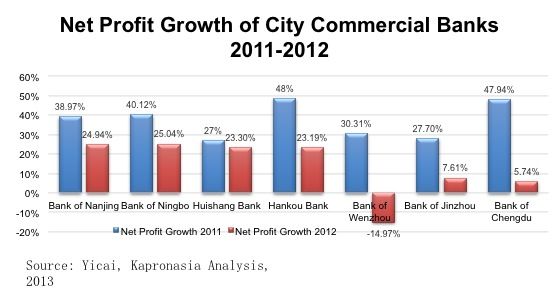

According to the annual reports released by city commercial banks, a lot of city commercial banks’ net profit growth rates in 2012 have shown a slowing down trend compared to 2011. For example, in 2011, both net profit growth rates of Hankou Bank and Bank of Chengdu were close to 50%, however, both of them shown a dramatic decrease as the end of 2012. Also, the net profit growth of the two listed city commercial banks - Bank of Nanjing and Bank of Ningbo, are showing a significant decline in 2012.

Lower net profit is putting a lot of pressure to Chinese commercial banks in 2013, and the figures implies that city commercial banks have to seek for new business and products to reboot high profit in 2013.

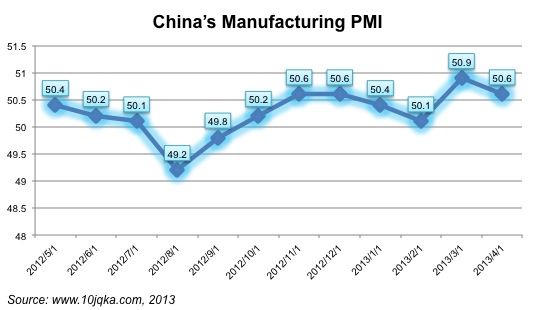

The latest Chinese manufacturing PMI is 50.6, declining by 0.3 point from March. From May 2012 to April 2013, this PMI figure has hovered the important line of 50 which is the watershed between economic growth and shrinkage. It signals that the growth of Chinese manufacturing economy is still fluctuating, largely because of the transformation and reformation of Chinese manufacturing industries during this period. The trend is expected to continue in the future so we will likely see continued fluctuations.

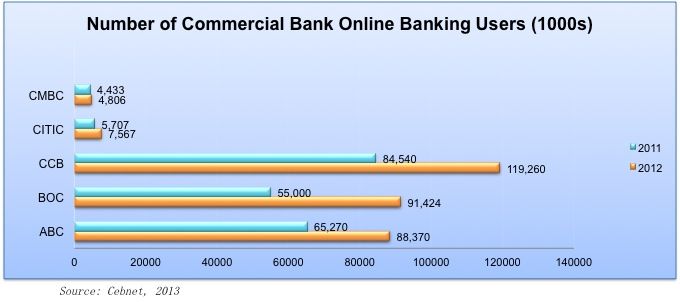

As the end of 2012, the total number of Chinese online banking registered users reached about 489 million. More specifically, according to the data released from Cebnet, CCB’s online banking customers increased to 119.26 million, jumping by 41% from 2011 to 2012. The number of BOC’s online banking customers has reached to 91.42 million, with a year-on-year growth rate of 66%.

Because of the dramatic increase in the number of online banking users, banks such as ICBC and CCB have launched more innovative personal banking services such as social insurance and wealth management services.

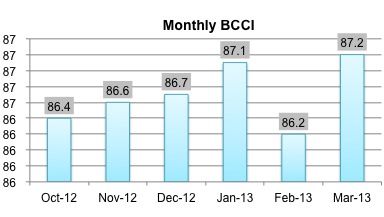

Recently, China UnionPay (CUP) and Xinhua News Agency jointly released the Xinhua • CUP Bankcard Consumer Confidence Index (BCCI) for March 2013. It shows that the BCCI is currently at 87.20, growing by 1% month-to-month and 0.43% year-on-year. Generally, the more consumption expenditure on non-necessities, the better macroeconomic situation and personal income reflected, and the more optimism consumers hold towards the future economic situation and personal income.

Based on the transaction information of bankcard consumption by urban residents, this BCCI reflects the confidence level of the consumers towards macro-economy by analyzing the changes to the structure of the bankcard consumption expenditure (mainly the change in the proportion of non-necessities to total consumption amount). Chinese government’s further push on domestic consumption will continue to drive the steady growth of BCCI.

According to Beijing’s government, the total transaction value of e-commerce in Beijing, one of biggest cities in China, grew by 45% to 550 billion RMB in 2012. Beijing’s e-commerce market is characterized by its high transaction volume, which has prompted half of China's top 10 e-commerce companies set up headquarters in Beijing in often in one of the two national e-commerce industry zones which attract a great number of small and medium e-commerce firms. Beijing’s government expects that its e-commerce transaction value will grow at 22% CAGR and hit 1 trillion RMB in 2015, which will account for 60% of Beijing’s GDP.

According to the CBRC, China’s commercial banks announced a total net profit of 1.24 trillion RMB in 2012, with the total net profit of the 16 listed banks comprising 1.03 trillion of that total. Among these 16 listed banks, the five major banks ICBC, ABC, BOC, CCB, and BOCom earned 239, 145, 139, 194, and 58 billion RMB respectively in 2012. China Merchants Bank (CMB) made 45.3 billion RMB net profit in 2012, topping other joint-stock banks. Bank of Beijing, as the leading city commercial bank in China, earned 11.7 billion RMB net profit last year. However, the overall net profit growth rate of China’s commercial banks has declined compared to 2011 apparently due to the process of interest marketization which has deceased interest based revenue recently.

There are two main sub-industry categories that QFIIs seem to be investing in in China's A-Share market: the mechanics and food & drink manufacturing industries. During the first quarter of 2013, there was a slight decline of 1.55% in the QFII shareholdings in the mechanics manufacturing industry and a 5.78% increase in the food & drink industry.

Wealth management refers to a type of financial analysis, financial planning and management service that banks provide to high net worth individuals. Banks have the obligation to return certain profit by managing customers' funds in an agreed period of time.

Recently, Alipay, China’s largest third-party payment company, released its sound wave payment mobile product, which is the first time that “sound payments” have been commercialized in China. Customers can now pay for goods from the vending machines deployed by Alipay in Beijing’s subway through the sound wave payment.

According to the China Securities Journal, the quality of credit assets is again appearing as an issue for Chinese banks. The latest annual report shows that the non-performing loan (NPL) balance and non-performing loan (NPL) ratio both increased in 2012, a sharp move from the “double decreasing” in both NPL balance and NPL ratio in the previous years.

According to the China Securities Journal, the quality of credit assets is again appearing as an issue for Chinese banks. The latest annual report shows that the non-performing loan (NPL) balance and non-performing loan (NPL) ratio both increased in 2012, a sharp move from the “double decreasing” in both NPL balance and NPL ratio in the previous years.

The total NPL balance in the 11 listed banks was ¥385.38 billion in 2012 with a YOY growth rate of 8.1% compared to ¥356.6 billion in 2011. China Construction Bank believes the upward trend in NPL is due to the macroeconomic fluctuations in manufacturing, wholesale and retail trade, and real estate.

More...

The trust industry is currently the fastest growing segment in China's asset management industry so far in 2013. In Q4 2012, the total trust AUM was about US$1.195 trillion. At the end of Q1 2013, this number had reached about US$1.395 trillion representing a growth rate of about 16.7%. That growth rate is actually faster than the growth rate of bank loans / deposits, market growth of the securities market, bonds, funds and insurance industry.

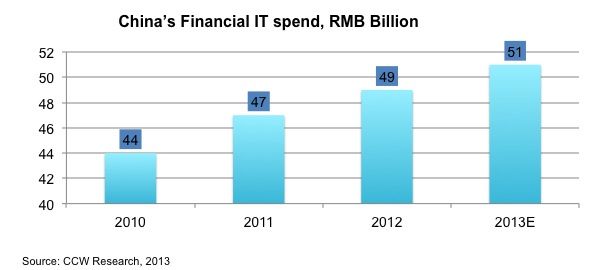

According to CCW Research, a local Chinese IT market research company, China’s financial industry IT software spend in 2012 grew to 49 billion RMB and the spending will keep a steady growth in 2013. Banking segment spend is a key driver, making up about 72% of total spend. Comprehensive risk management and big data are the main IT focus areas for banks.

As securities companies continuously launch new business, CCW estimates that IT spending on new business-related solutions in the securities sub-segment will increase considerably in future.

For insurance companies, the overall IT infrastructure is still very nascent. Large players will invest more money into the development and update of core systems.

Last month, China Mobile, the biggest mobile network operator (MNO) in China, and China UnionPay (CUP) unveiled their latest mobile payment product – “Mobile Wallet”- at MWC 2013 (Mobile Word Congress, the world’s premier mobile industry event).

Kapronasia's latest report Trading China - A Look at the Issues and Opportunities in China's Capital Markets is now available in the research reports section of the Kapronasia website. The report, sponsored by Equinix, is a detailed look at the challenges and opportunities in China's capital markets. The report is free, but does require registration to download. For more information on the report, please look in the research reports section of the website above.

In a recent article, the Wall Street Journal wrote about how although mobile payments are slow to take off in China, telephone or 'fixed-line' payments are actually doing quite well and actually hugely dwarfs mobile payments. When you consider the history of the 5 major banks and their alignment with particular sectors, it's no surprise that the Agricultural Bank of China would be leveraging this kind of business model, but what is interesting is the way that the model completely avoids mobile payments. It's almost as if the bank (industry?) in China is saying 'ok, so no standards on mobile, we'll innovate with what we have.' Which is actually not tremendously different that what we're seeing in other markets where the adoption of a consistent mobile payments standard seems inconsistent at best...

In a recent article, the Wall Street Journal wrote about how although mobile payments are slow to take off in China, telephone or 'fixed-line' payments are actually doing quite well and actually hugely dwarfs mobile payments. When you consider the history of the 5 major banks and their alignment with particular sectors, it's no surprise that the Agricultural Bank of China would be leveraging this kind of business model, but what is interesting is the way that the model completely avoids mobile payments. It's almost as if the bank (industry?) in China is saying 'ok, so no standards on mobile, we'll innovate with what we have.' Which is actually not tremendously different that what we're seeing in other markets where the adoption of a consistent mobile payments standard seems inconsistent at best...