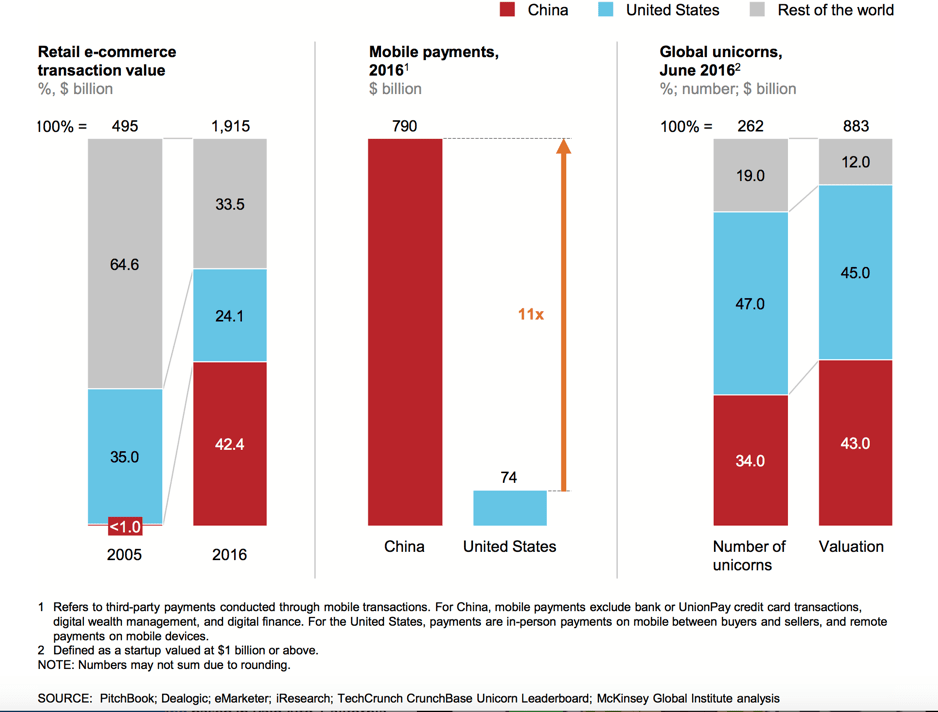

Despite the rarity of these exceptional companies, China has managed to amass an incredible number of unicorns over the last decade. So much so in fact, that according to McKinsey, one in three of the world’s 262 unicorns is Chinese, commanding 43% of the global value of these companies, with firms such as Ant Financial leading the pack with a recent USD $70bn valuation.

As seen in the charts above, the impressive number of Chinese unicorns coincides with an unprecedented rise in both e-commerce transaction value and mobile payments within the country. The value of China’s e-commerce transactions is today estimated to be larger than the value of those of France, Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States combined.

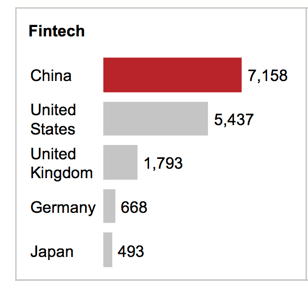

Chinese start-ups are equally boosted by the fact that investors are enthusiastic and tend to have high expectations about the growth potential for the countries’ start-ups. In the fintech category alone, 9 of the 23 privately held unicorns in the world are based in China, and they account for more than 70% of the total valuation of fintechs worldwide. One perfect example of the relative excitement and optimism for growth generated by digitally oriented start-ups in China, is Mobike and Ofo. According to McKinsey, the combined valuation of the two Chinese bicycle-sharing companies of around $6 billion, is higher than that of the top two airline companies in South Korea, valued at about $5 billion.

Venture capital investment in leading technologies, 2016 ($ million)

SOURCE: PitchBook; McKinsey Global Institute analysis

Another key explanation for the rise in Chinese unicorns is the relative immaturity of the traditional financial system at the time, with many SME’s not being adequately served by banks. This therefore lead to the growth of the world’s largest alternative and highly innovative lending industry. This circumstance, coupled with the fact that China has a massive digitally connected consumer market (695 million mobile web users in 2017, according to eMarketer) and hence a large pool of compatible customers for its growing firms. The growth of China’s e-commerce shows no signs of slowing down either, with sales likely to top $1.1 trillion this year, according to eMarketer, or more than twice the figure in the United States and 200 million more Chinese shoppers are forecast to move online by 2020.

Despite all of this, there are some looming threats to China’s unicorn dominance. Concentrating on a single market, even one as big as China’s, could prove risky in the event of a serious economic downturn. Most Chinese firms are aware of this however and have made efforts to expand their services and products into markets abroad. Mobike for example, recently launched in Manchester, England, its first bike sharing service outside of Asia.

China’s large market can also lead to insurmountable competition. Easy money has spurred fierce competition and price wars in areas like smartphones, taxi-hailing and food delivery. Subsidies are rife, as companies seek to win customers over to new ideas, or to outspend rivals into submission, as Didi did to defeat Uber. Companies have therefore risen to the top through aggressive short term tactics, yet failed to follow up on their early successes due to an eventual need to turn a profit. The handset maker Xiaomi for example, once accorded a $46 billion valuation, briefly ruled by selling cheap, slick mobiles online. It has however now tumbled to fifth place as rivals offer even bigger bargains. Its phones have low single-digit operating profit margins, compared to the iPhone's high 30% margins.

Another issue faced by Chinese start-ups is regulation, a crackdown on peer-to-peer lending and online "wealth management products" has probably delayed flotations by both Ant and Lufax, for example. However, despite the future risks posed by regulation, China has previously allowed long periods without regulatory intervention in order to foster growth and allow firms to experiment. While the response of regulators lagged behind market developments, China’s internet giants were relatively free to test and commercialize products and services in order to gain critical mass. For example, regulators took 11 years after Alipay introduced online money transfers in 2005 to set a cap on the value of the transfers. According to EY, China is formalizing a harmonious relationship between banks and fintech and is increasingly at the forefront of regulatory developments within FinTech, signalling a dramatic change in the origin of where regulatory standards may emerge from.

The worry is that the ‘golden era’ of regulation free business is now a thing of the past and that the coinciding period of unicorns appearing regularly is over. In China’s more developed digital environment, the government has unveiled new regulations. The first cybersecurity law, which became effective in June 2017, includes protection of personal information, security requirements for network operators, and restrictions on personal and business data transfer. Although no country is seemingly close to matching the number of Chinese unicorns, it will be interesting to see how Chinese firms adapt and whether they continue to grow at the pace we have seen up until now.