China Capital Markets Research

Will Chinese stocks be able to remain listed in the US?

There is a growing list of Chinese companies that could be forced to exit U.S. stock exchanges under legislation passed in 2020. The legislation requires all public companies in the U.S. to comply with auditing requirements that Chinese companies have resisted due to Beijing’s own state secrecy laws. On March 30, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) added Baidu to the list. A total of 11 Chinese companies facing delisting have been named so far.

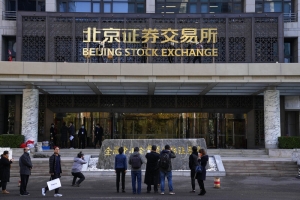

Assessing the Beijing Stock Exchange’s prospects

Does China need yet another stock exchange? That has been the question of many of our minds since first hearing about the Beijing Stock Exchange, a rejigging of the existing over-the-counter New Third Board. It came about amid a push by Chinese President Xi Jinping to boost onshore capital markets and create an enduring fundraising channel for China’s chronically underfunded small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). To that end, the minimum market cap to join the Beijing exchange is just US$31.3 million, significantly less than China’s other exchanges.

The reshoring of Chinese IPOs

It is hard to believe that during the first half of 2021 Chinese IPOs in the United States raised a record US$12.4 billion, per Dealogic’s estimates. That was the boom before the bust, which had been brewing for a long time but came to the fore with the disastrous debut of Didi Chuxing on the NYSE. Like Alibaba’s nixed IPO heralded a widespread regulatory crackdown on fintech, Didi’s is doing the same for Chinese IPOs overseas.

Hong Kong may be attracting the lion’s share of offshore listings by Chinese companies, but New York is no slouch. In fact, for all the talk of U.S.-China decoupling, the world’s most liquid capital markets retain significant appeal for Chinese companies. According to Dealogic, 36 Chinese companies had raised US$12.59 billion in U.S. markets as of June 30, a half-year record.

U.S.-China financial decoupling is an odd thing. Instead of a linear progression in which Chinese firms gradually eschew going public in the US and delist from its stock exchanges, we see some Chinese companies continuing to seek exits on the Nasdaq or NYSE, while others are seeking secondary listings in Hong Kong as a hedge against forced delisting. Still others are actually being forced to delist like the telecoms giant China Mobile, which is now looking at a new listing on the Shanghai Stock Exchange.

Fintech crackdown slows Shanghai STAR board's momentum

Before Ant Group’s IPO was nixed, the Shanghai STAR board was red hot. Since then, it has cooled off considerably. Not only is Ant’s IPO in limbo, but other Chinese tech companies are scuttling their plans to go public, one after the next. Ant is the bellwether for the market, whether it is a bull or bear. Data compiled by Financial Times show that 76 firms suspended their IPO applications in March, more than twice the number in February. Overall, 168 companies have put their plans to go public on ice since November.

U.S.-China financial tensions flare anew

To delist or not to delist: That is the question. The New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) could not seem to make up its mind earlier this month, delisting three Chinese state-owned telecoms stocks (China Mobile, China Telecom and China Unicom Hong Kong), reversing course, and then finally deciding that the three firms should be delisted after all. The professed reason for kicking the companies off the NYSE is they have ties Chinese military and threaten America's national security. The impact on their market capitalization will likely be limited as their trading volume is much higher in Hong Kong than New York. More forced delistings of Chinese firms could occur in the waning days of the Trump administration though.

JD Digits' IPO may have to wait

The suspension of Ant Group's blockbuster IPO has cast a shadow over China's fintech industry as online microlenders scurry to figure out how to meet tough new capitalization requirements. JD Digits, the fintech unit of e-commerce giant JD.com, is one of the firms most affected by the nixed Ant IPO. JD Digits filed in September to list on the Shanghai STAR board, a deal that was expected to raise up to US$3 billion.

Suspended Ant IPO creates uncertainty for Chinese fintechs

With the suspension of Ant Group's IPO, Beijing is once again signaling that its patience for fintech-induced disruption has limits. In the past, Chinese regulators throttled entire fintech industry segments - cryptocurrency and P2P lending - that they deemed excessively risky to the financial system and a threat to social stability. To be sure, Ant Group plays an integral (some would say peerless) role in the Chinese financial system which makes it very different from P2P lenders and crypto firms. However, Beijing places a premium on controlling systemic financial risk. No company can expect the enthusiastic backing of regulators if it appears too gung-ho about disruption and somewhat contemptuous of the system. China officially remains a socialist market economy, lest fintechs or their investors forget.

Why is Lufax planning a U.S. IPO?

Amid clouds of a U.S.-China financial war, Hong Kong is fast becoming the default for Chinese fintech IPOs. The former British colony offers liquid capital markets both close to both home and global investors. But there are exceptions. Lufax, one of China's largest online wealth management platforms, is reportedly instead eyeing a New York IPO that could raise up to US$3 billion. If Lufax moves fast, it can list in the U.S. before new rules go into effect that may prevent Chinese firms non-compliant with American accounting standards from listing on U.S. exchanges.

More...

Shanghai's STAR board shakes up China's capital markets

Shanghai's STAR board is introducing a more market-driven approach to China's initial public offerings. Listing on the STAR market is more streamlined than the traditional process in China, where new listings are subject to an informal price cap of 23 times earnings and a 44% ceiling for first-day gains. Before the Shanghai STAR Board was launched it July 2019, it could take many years before companies' plans to go public were approved. Now a flurry of tech listings on the Shanghai STAR market are shaking up China's capital markets.

2 listings are better than 1 for Ant IPO

For the IPO of China's fintech giant Ant Group, two listings are better than one. Instead of going public only on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange or the Shanghai STAR Market, Ant plans to list on both. Ant has not disclosed the size of its coming IPO, but the firm is reportedly valued at US$200 billion, up from US$150 billion during its 2018 fundraising. Ant reportedly plans to sell 10% of its shares through the twin listing, which could come this year or in 2021. An uncertain market outlook will inevitably weigh on timing.

London may attract more IPOs from China

As tensions between the U.S. and China flare up in the financial sector, the future of Chinese fundraising in America's capital markets looks uncertain. Hong Kong has benefited, attracting a growing number of Chinese tech IPOs and secondary share listings from juggernauts like Alibaba and JD.com. Another possible winner in the U.S.-China financial tussle could be London, which began operating the London-Shanghai Stock Connect scheme in 2019.

What went wrong at China's Starbucks rival Luckin?

In early April, China's Starbucks rival Luckin Coffee was revealed to be a paper tiger. The company that was supposedly giving the U.S. coffee giant a run for its money in the world's largest consumer market had literally fabricated its success. To be sure, Luckin's 4,500 China stores - exceeding Starbucks' 4292 - were no mirage. But the company's sales figures were bogus. On April 2, Luckin publicized the results of an internal investigation showing RMB2.2 billion (US $311 million) in fraudulent sales from the second to the fourth quarter of 2019.