Asia Banking Research

What has Sea got to lose? US$433.7 million

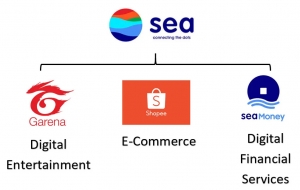

Sea Group just can’t lose when it comes to investor sentiment, even though the company’s losses widened on an annual basis to US$433.7 million in the second quarter from US$393.5 million a year earlier. The day before it reported Q2 earnings, Sea’s share price was about US$291 and as of August 23 it had reached US$315. Over the past year, the stock has risen more than 105% while Sea’s market cap now stands at US$168 billion.

Why is the Philippines back on the FATF grey list?

The Philippines has returned to an unenviable position: It is once again one of the only East Asian countries on the Financial Action Task Force’s (FATF) Grey list, alongside Cambodia. Countries on the grey list have been flagged by FATF for insufficient anti-money laundering and/or counterterrorism financing controls. Being on the list creates regulatory headaches for financial institutions – such as higher interest rates and processing fees – and can be detrimental to a country’s business environment.

Taiwan’s virtual banks arrived at the right time

With 37 retail banks for a population of 23.5 million, Taiwan is not the easiest market for digital banks to crack. Just about every Taiwanese adult has a bank account; in fact, many have more than one because of the tendency of companies in Taiwan to require employees to open a bank account with the company bank. Nevertheless, near ubiquitous smartphone penetration and the popularity of certain platform companies’ ecosystems offer digital banks an opening in Taiwan, especially given the effect of the pandemic on people’s banking habits.

AirAsia’s super app project may have wings

We have to hand it to AirAsia: They tell the super app story well, probably better than some of the others whose task is less daunting than the beleaguered airline’s. Indeed, AirAsia is not a high-flying tech company aiming to use fintech to take its valuation and exit to the next level, but an airline facing an existential crisis wrought by the never-ending coronavirus pandemic. If AirAsia pulls off its transformation, it will stand as one of the great turnarounds in recent Asian corporate history, and perhaps pave the way for a new breed of platform company.

Will Revolut’s travel app give it an edge in Asia?

Revolut is the biggest neobank most of Asia has never heard of. Try as it might, Revolut just has not been able to make much of an impact in any APAC market yet, which is not a huge surprise given the amount of competition it faces and its distant home base in the UK. Revolut needs something to make it stand out from the crowd in APAC. Its new travel app Stays might be just what the doctor ordered.

Singapore’s largest banks have a better-than-expected Q2

It would have been difficult for Singapore’s Big 3 banks – DBS, OCBC and UOB – to beat their performance in the first quarter. That holds especially true for DBS and OCBC, which both posted record earnings in the January-March period. So while all three banks saw earnings fall in the second quarter on a quarterly basis, they still turned in a solid performance that beat analysts’ expectations.

Why are Grab and Bukalapak teaming up?

Indonesia is fast becoming the most hotly contested of Southeast Asia’s digital services markets. No other market is both as large and untapped. With that in mind, Singapore’s Sea Group and hometown favorite GoTo have made significant plays in recent months. The former acquired Bank BKE, while Gojek upped its stake in Bank Jago and then merged with Tokopedia. Not to be outdone, Grab is teaming up with Tokopedia's rival Bukalapak. This move finally brings e-commerce into the Singaporean firm's ecosystem and strengthens the hands of both Grab and Bukalapak as they prepare to go public.

If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em. That seems to be true in just about every market that has introduced digital banks, and it is a two-way street. Hype about the challengers unseating incumbents tends to give way to a more nuanced reality in which there is some room for cooperation. In Australia, where four large banks have long dominated the market, the incumbents are steadily increasing their cooperation with fintechs in a bid to strengthen their digital offerings.

Viva Republica and Big Fintech in South Korea

Big Tech may have reached an apex in the United States and China, but in South Korea it is ascendant. In a country where chaebols have long been dominant, it is not hard to imagine internet companies – and indeed fintechs in particular – taking a similar path. And that is exactly what is happening. First, Kakao became a fintech giant, and now it is Viva Republica’s turn. The company, which operates Toss, the largest fintech app in South Korea, recently raised US$410 million at a valuation of US$7.4 billion.

Sea Group is one of the most successful loss-making companies in the world outside of private markets. Sea lost an astronomical amount of money in the first quarter of the year: US$422 million. That is not normally cause for celebration among listed companies, but its revenue also grew 147% year-on-year to US$1.76 billion. Investors are cheering: Sea’s stock price has risen more than 300% to US$283 over roughly the past year. Helping to drive that bullish investor sentiment are expectations about Sea’s potential in Southeast Asia’s nascent but fast-growing digital finance space.

More...

Will Traveloka’s fintech gambit succeed?

If there ever was a “We are all fintechs now” moment, it must have been earlier this year when Indonesia’s online travel unicorn Traveloka stepped up its rebranding as a digital financial services provider. Skeptics could have been forgiven for rolling their eyes. Yes, the pandemic has hit the travel industry hard and companies like Traveloka need to rejig themselves or they may not survive. On the other hand, not every platform company is suited to reinvent itself as a fintech.

Why has Kakao been successful as a fintech?

Many of the world’s preeminent platform companies have tried to reinvent themselves as fintechs. Outside of China, South Korea’s Kakao is the only one that is an undisputed success. Kakao boasts South Korea’s largest e-wallet, with 36 million users, and leading digital bank. Both will go public in Korea in August and are likely to raise US$1.4 billion and US$2.3 billion respectively. The speed of Kakao Bank’s swing to profitability (it took just two years) – paving the way for the IPO just four years after its founding – has been remarkable by industry standards.

Fly the super app skies with AirAsia

Just about every major tech company now wants to be a fintech, super app or both. What makes AirAsia different is that its core service has nothing to do with the internet or banking. Indeed, AirAsia is an airline that happens to have a digital services arm. The Malaysia-based firm probably would have stayed that way had it not been for the coronavirus pandemic and its devastating effect on airlines and the travel industry. AirAsia is now going all in on its super app gambit, applying for a digital banking license in Malaysia and acquiring Gojek’s Thailand business.

In both Singapore and Hong Kong, digital banks are nice to have. In Malaysia, whose digital banking application period ended on June 30, the need for digibanks is somewhat greater. But in the Philippines, where 71 million adults remain unbanked and 1/3 of municipalities lack a banking presence, the need for neobanks is more pressing. With that in mind, the Philippines’ central bank is approving digital banks’ applications on a rolling basis in the hope of reaching key financial inclusion targets by 2023. Tencent-backed Voyager Innovations and RCBC are the two most recent entrants to the country’s digital banking race.